Kadeem’s Story

Patient Voices

Kadeem

Sickle Cell Disease

Boston, Massachusetts | Born May 1989

“It’s hard for sickle cell patients to get their voices heard… The world doesn’t see us. We have an invisible disability.”

It’s springtime in Boston and blossoming trees line the streets, hovering over cracked sidewalks, providing shade. Kadeem walks peacefully through the neighborhood in which he lives––the same one in which he grew up––basking in the warm air, breathing in the scent of winter’s passing. On days like this, anxious thoughts about his disease are kept at bay. He can temporarily forget about the pain, hospitalizations, medications, and the dread that comes with living with sickle cell disease.

Sickle cell disease (SCD) is a genetic condition that leads to abnormally shaped red blood cells. SCD patients typically suffer from serious clinical consequences, which, among others, may include anemia, pain, infections, stroke, liver disease, and reduced life expectancy. Kadeem was diagnosed when he was three years old, following hospitalization from a virus he had contracted. Kadeem’s older brother had already been diagnosed with SCD six years earlier. “I remember getting horrible pain in my stomach, back, and chest as a kid,” he says. Curled up with a pillow against his body, Kadeem rocked back and forth in bed unaware of how many days or even weeks of school he had missed. His parents did everything they could think of—they wrapped him tightly in blankets, applied heating pads to needed areas, pored over medical research about sickle cell, and sought out top-notch medical care. As he grew older, Kadeem experienced these crises approximately every three months, the pain emerging suddenly, anywhere and everywhere in his body––his back, his stomach, his joints, and his head. Crises began to intensify to the point that trips to the emergency room were required in order to receive IV drips of medication until the pain subsided enough to be managed with oral medication, which he often needed for weeks.

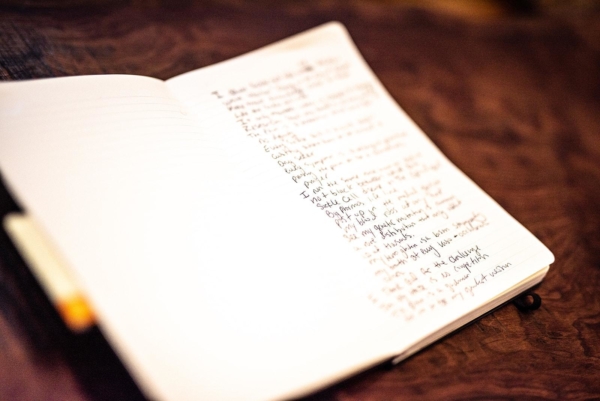

As a teenager, Kadeem navigated back and forth between normal functioning and periods of seclusion due to the crises, times at which he would turn inward. He was an avid reader and lover of music, so when imprisoned by pain, he began to experiment with letting his mind play with words, rhythms, and sounds. Over time, bits of phrases were gathered into verses, which he wrote down in a small journal he kept next to his bed.

“I’m tired of these countless nights where I wake up and

I can’t walk.

How can a cell so small, feel like I’ve been stoned by rocks.”1

Expressing himself felt liberating. Soon, poems about living with sickle cell began to pour out of him, filling up pages and then stacks of journals. When a friend invited him to a poetry slam, Kadeem watched in awe and excitement as he witnessed the power of combining poetry with voice. Inspired, he began to perform his work. “It’s hard for sickle cell patients to get our voices heard,” he says emphatically. “Our pain is a subjective experience that can’t be quantified or studied mathematically. The world doesn’t see us. We have an invisible disability. That’s what my poetry aims to express.”

Kadeem places his rounded hands softly on his knees, a quiet and delicate gesture that contrasts the difficulties and intense pain he describes. “Disability,” he says carefully, enunciating the sound of each syllable. “When I was in college, far away from home for the first time,” he says, “that’s when it finally occurred to me that I had a disability.” The crises caused him to miss classes, miss exams, and interfered with his study time. During spring break of freshman year, Kadeem experienced pain in his stomach that he describes as the worst pain he ever had. He flew home and went to Boston Children’s Hospital where doctors performed an ultrasound of his pancreas and found gallstones. “I had to have my gallbladder removed which meant moving back home. I dropped out of school. I was devastated.” Determined to push forward, he knew he needed a different approach. “I realized that I needed to advocate for myself as someone who required accommodations in order to succeed.” He enrolled as a freshman at American International College with a plan—he would approach his professors ahead of time and explain his illness as a disability. He would outline the extra time, patience and effort he would need to stay caught up. The first day of class, he walked in with newfound confidence as an empowered self-advocate. Kadeem went on to earn a B.A. in communications and English at American International College and an MFA in poetry at Adelphi University.

Kadeem places his rounded hands softly on his knees, a quiet and delicate gesture that contrasts the difficulties and intense pain he describes. “Disability,” he says carefully, enunciating the sound of each syllable. “When I was in college, far away from home for the first time,” he says, “that’s when it finally occurred to me that I had a disability.” The crises caused him to miss classes, miss exams, and interfered with his study time. During spring break of freshman year, Kadeem experienced pain in his stomach that he describes as the worst pain he ever had. He flew home and went to Boston Children’s Hospital where doctors performed an ultrasound of his pancreas and found gallstones. “I had to have my gallbladder removed which meant moving back home. I dropped out of school. I was devastated.” Determined to push forward, he knew he needed a different approach. “I realized that I needed to advocate for myself as someone who required accommodations in order to succeed.” He enrolled as a freshman at American International College with a plan—he would approach his professors ahead of time and explain his illness as a disability. He would outline the extra time, patience and effort he would need to stay caught up. The first day of class, he walked in with newfound confidence as an empowered self-advocate. Kadeem went on to earn a B.A. in communications and English at American International College and an MFA in poetry at Adelphi University.

In his graduate-school years, however, Kadeem found himself confronted by a new obstacle in the very place he had always counted on for care and relief––the hospital. “When the opioid crisis swept across the country with full force [in the early 2000s],” he says, “I was suddenly discriminated against at the hospital. I would come to the ER in intense pain and they thought I was an addict. They treated me like I was seeking drugs. I was afraid to ask for pain meds because of the way I was being treated.” New protocols and legislation had been put into place. Even with his regular physician, who knew him well, there was additional paperwork to complete and added hoops to jump through. “To this day, few people understand how sickle cell patients are victims of the opioid crisis,” he says.

During a recent visit to Atlanta, where Kadeem was attending The Sickle Cell Consortium General Assembly and Leadership Summit, he was suddenly hit with an intense crisis in his back and legs. He bent over sweating, shaking, and moaning for help. He called the executive director of the consortium who then called the ambulance. “When we arrived at the hospital, they would not give me a room. I heard the EMTs arguing with the hospital to get me treated. My friend Nikki, who also has sickle cell, was yelling at the medical staff. Once I got a room, they were hesitant to give me pain medications.” Fear rushed through his body in waves.

“I need a doctor

a warrior, can’t find a hospital bed

Is it too late for god to build my blood out of stars?”2

It took eight hours for the medical staff to administer an IV. Eight hours of excruciating, writhing pain. A half-hour in, a peaceful calm spread across his body. When the pain subsided, he could see that the delay in treatment was, in fact, due to an overcrowded hospital and doctors that lacked knowledge in how to treat his pain, given his symptoms of fever and high white blood cells. Still, the trauma of being denied medication when he desperately needed it stayed with him for weeks. The memory of grasping the railings of the hospital bed repeated in his mind over and over, waking him up at night sweating in panic.

As if catching his breath from the retelling of the story, he puts one hand on his chest. He pauses, closes his eyes and holds a few seconds of silence. “I have found myself recently on a spiritual awakening,” he says. “I have been meditating.” He speaks of how breathwork has helped him center himself in the weeks following the trauma in Atlanta. “I’m getting older. Some of my friends with sickle cell have passed away and they were my age. I work to live in the present moment. I don’t want to live with anxiety. I aim to appreciate the good in my life.”

Over the years, through poetry and advocacy, spreading awareness about SCD has become Kadeem’s medicine of choice. He is currently pursuing a Ph.D. in medical humanities. For his thesis, he is collecting 20 personal narratives from people living with SCD, with the intention of weaving the narratives together in order to elucidate a story of collective experience. “I’m crawling on my tongue to finish my thesis,” he laughs, noting that every class he has ever taken required him to take an incomplete. “I want to educate the world about the challenges of living with sickle cell, but at the same time, I don’t want people to see sickle cell as the demon. This disease is my guardian angel. It makes me live in the here and now.”

“The pain is a guidance

for me to be my greatest version”3“I may be born without a dream

But every day, I’m living to succeed.”4

Kadeem’s poetry has earned him several accolades including the Donald Everett Axinn Award in poetry. He is currently a second-year fellow at Cave Canem, a prestigious foundation for African American poets.

1,4 Gayle, Kadeem. “It’s a Living”

2 Gayle, Kadeem. “Waiting Room”

3 Gayle, Kadeem. “Greatest Version”